From all Points of the Southern Sky: Photography from Australia and Oceania

Southeast Museum of Photography - Daytona, Florida September 22 - December 16, 2020

Torika Bolatagici, Jane Brown, Peta Clancy, Stephen Dupont, Silvi Glattauer, Leah King Smith, Katrin Koenning, Sonia Payes, Kate Robertson, Kurt Sorensen, Angela Tiatia, Tobias Titz, Anne Zahalka

Curated by Ashley Lumb

press: Aesthetica, this is tomorrow, Australian Arts Review, Photomonitor, L’Oeil de la Photographie

360 video walkthrough, narrated by Australian voice artist Ming-Zhu Hii

Talks: Zoom curator + artist talk at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, December 2020

Commissioned artist videos

This year has been one of national and global crises. In Australia, the most catastrophic bushfires ever recorded reached a destructive peak in early 2020, exacerbated by climate change and a rapidly warming planet. George Floyd’s death sparked outrage and international protest as he became the latest African-American victim of police brutality, eliciting renewed calls to purge Western institutions of systemic racism. Meanwhile, Coronavirus – officially granted pandemic status in March – has radically disrupted the social and economic fabric of life worldwide. But, if anything positive can be said to have emerged as a consequence of these adversities – and the work of the photographers featured here insists that it must – it’s a burgeoning consciousness of collective action and shared responsibility.

The thirteen artists in From all Points of the Southern Sky: Photography from Australia and Oceania incisively explore the Australian continent – its dark colonial history, indigenous cultures and violent repressions – as well as turning their gaze on the neighboring countries of Oceania. Jane Brown, Peta Clancy, Leah King Smith, and Kurt Sorensen drag Australia’s contentious past into the light of the present, visualizing the ghostly legacy of colonialism – its haunted landscapes and criminal beginnings – while Anne Zahalka, Stephen Dupont, Katrin Koenning, and Sonia Payes bear witness to the devastating impact of human-induced climate change. Australia’s increasingly extreme bushfires are evidenced by Koenning’s starkly beautiful triptych Lake Mountain (2018), as well as Dupont’s heartrending images of the ‘Black Summer’ of 2019/2020, while Zahalka’s digitally altered archive photos of museological dioramas offer a more truthful representation of nature in an Anthropocene age. In comparison, Silvi Glattauer’s photogravure prints of Bittangabee Bay National Park, beautified with jade-colored pieces of Japanese Gampi paper, evoke a more enchanting time and place.

Employing a range of media and photographic approaches – wet collodion negatives, Polaroid film, archival imagery, video works, and singular soundscapes – From All Points of the Southern Sky repeatedly turns our attention back to the unresolved issues of our time. The disavowed history of colonialism and the marginalization of Indigenous Australians is one such potent theme, tackled productively by Tobias Titz in Right to be Counted (2007) and Farewell 665 (1998-2020), and both of which foreground the creative agency of immigrants and Aboriginal Australians. Kate Robertson utilized a similarly collaborative methodology for Recording the medicinal plants of Siwai, Bougainville (2016). The indigenous Siwai people of Papua New Guinea shared their knowledge of local flora and traditional medicine with the artist, and, under her guidance, produced vibrant photograms celebrating the plants’ healing properties.

Inextricable from discussions of colonization is the issue of race, explored in two visually divergent but thematically complimentary videos. Torika Bolatagici’s Ecology/Economy (2013) is a plaintive critique of the commodification of the Fijian body that poignantly juxtaposes indigenous bodily practices – an infant’s wellbeing cultivated by parental massage – with the death of Fijians in the military conflicts of other countries. But where that film is lyrical and languorous, Angela Tiatia’s Interference (2018) compresses a sensuous barrage of imagery into just over a minute. Opening on three performers, who lithely move across a dark screen, dance and distorting visual effects briefly provide transcendence from the significations of the colour of their skin. The process of self-actualization, however, is hopelessly interrupted by a profusion of images culled from art history and popular culture: a psychic bombardment that dramatizes the struggle for personal autonomy.

Conveying a singularly Australian experience but one with innumerable global parallels, From all Points of the Southern Sky asserts that the only way to overcome our current crises is by drawing together: acknowledging the misdeeds of the past and taking united action to rectify them. Summing up a shared desire for social renewal is the word Makaratta, from the Yolngu language. It’s an incredibly apposite concept for our current moment. It means “the coming together after a struggle.”[1]

[1] https://www.smh.com.au/national/what-is-the-uluru-statement-from-the-heart-20190523-p51qlj.html [accessed April 11 2020]

Leah King Smith - Patterns of Connection, 1991 direct positive color photograph 103 x 105 cm

Leah King Smith initially set out to locate, rephotograph, print and catalogue all of the loose and hidden photographs of Aboriginal people from the Kulin Nations. These nineteenth century photos were taken by European photographers at a time when photography was used as a tool of scientific investigation and when indigenous races were the focus of this medium. However, Leah was so moved by the portraits she was compelled to change the project into something more personally engaging. “I was seeing the old photographs as both sacred family documents on one hand, and testaments of the early brutal days of white settlement on the other”, the artist has written. “I was thus wrestling with anger, resentment, powerlessness and guilt while at the same time encountering a sense of deep connectedness, of belonging and power in working with images of my fellow Indigenous human beings.”

Leah superimposed the portraits over her own photographs of the landscape, painting over parts and rephotographing them. This re-working of the photos recovered Aboriginal people from the archives and re-instated them in a more positive and spiritual realm. She reunited the sitter with the landscape to convey the importance of country to Aboriginal people and to remove the negative connotations and repression which were portrayed in the original photos.

Anne Zahalka

The Mallee, near Benetook in Sunraysia Region of Victoria, 2019 Source: Museums Victoria; Gnarnayarrahe Waitairie from Roebourne, Western Australia in the region of New South Wales, 2019 Source: Museums Victoria; Koala, Yarra River at Woori Yallock, Victoria, 2019. Source: Museums Victoria; Exotic Birds, 2017. Source: American Museum of Natural History archival pigment ink on rag paper, 80 x 80 cm

Working extensively across Australia and internationally for over thirty years, Anne Zahalka has regularly challenged stereotypical, picture-postcard representations of the continent: redressing a culturally skewed, often Anglocentric photographic record. In Welcome to Sydney (2002) she foregrounded the city’s vibrant multiculturalism, while Parliament House at Work (2014) documents the diversity of occupations essential to that iconic institution.

Adopting a similar intention, but with a different methodology, are her hand-colored and digitally-embellished archival photographs of museologial dioramas. Three such images are included here, from Wild Life, Australia 2019 and Wild Life 2006/2017, in which Natural History displays – ahistorical, romanticized depictions of nature – are subverted by the digital insertion of evidence of human activity. Aluminum cans litter pastel-colored landscapes, the habitats of native fauna are stripped bare, and painted backdrops blaze: rupturing an otherwise beatific aesthetic with the destructive reality of our Anthropocene age.

This wry visual dialectic, both amusing and critical, vividly elucidates the consequences of modern civilization’s exploitation of the natural world. In light of the ‘Black Summer’ of 2019/2020, in which roughly a billion animals died, Zahalka’s image of taxidermied koalas clinging to a tree against a background of roaring flames seems both poignant and prophetic.

Peta Clancy - Undercurrent, 2019 pigment inkjet prints 106 x 150 cm sound installation

Nineteenth century massacres of Aboriginal people in Australia are often hidden in secrecy and shame. To bring this hidden history to the surface, in 1988 the Koorie Heritage Trust compiled a Victorian Massacre map, showing the locations of known killings of Aboriginals by Europeans from 1836 and 1853. Artist Peta Clancy first became aware of this map in 2016 when she was researching her own indigenous heritage with the Bangerang people. Clancy applied for a permit to visit these massacre sites and what resulted was a year long residency which led her to collaborate with the Dja Dja Wurrung Elders and community to create a body of work that illuminates this hidden aspect of Australian colonial history.

This site of the massacre on the Dja Dju Wurrung Country gave rise to metaphoric interpretations: the bank of this river is now submerged, hence now burying further the possibilities of bringing the past to light. Clancy’s approach, however, reveals the duality at the heart of the work. She started by taking photographs of the landscape there, returning with the images printed out and installed in frames. While back at the site, she then cut into the photo to reveal a new view in the distance and re-photographed that scene through the frame. The two sides of this composite are wholly different, with varying degrees of sharpness, color, and exposure. The contrasts represent the past and present, the Aboriginal people and settlers, the submerged past and our uncertain future.

For Clancy, the physical act of cutting the photograph is comparable to the act of scarring. Although in the end the image is made whole again, a line still evident. The scarring is not viewed as negative though: “It’s not the actual cut, which has healed,” she says, “but a reminder of the violence of the incision”. Scarring is a sign of healing and past recovery, not future trauma.

Sonia Payes chromogenic prints various sizes

In Sonia Payes’ semi-abstract landscape photographs, nature is envisioned in an inextricable cycle of creation, destruction, and renewal. Underlying her visual depiction of environmental extremes is a fervent belief in nature’s ability to regenerate, to take on new forms. It’s an idea vividly expressed throughout the artist’s sculptural, filmic, photographic and multi-media work.

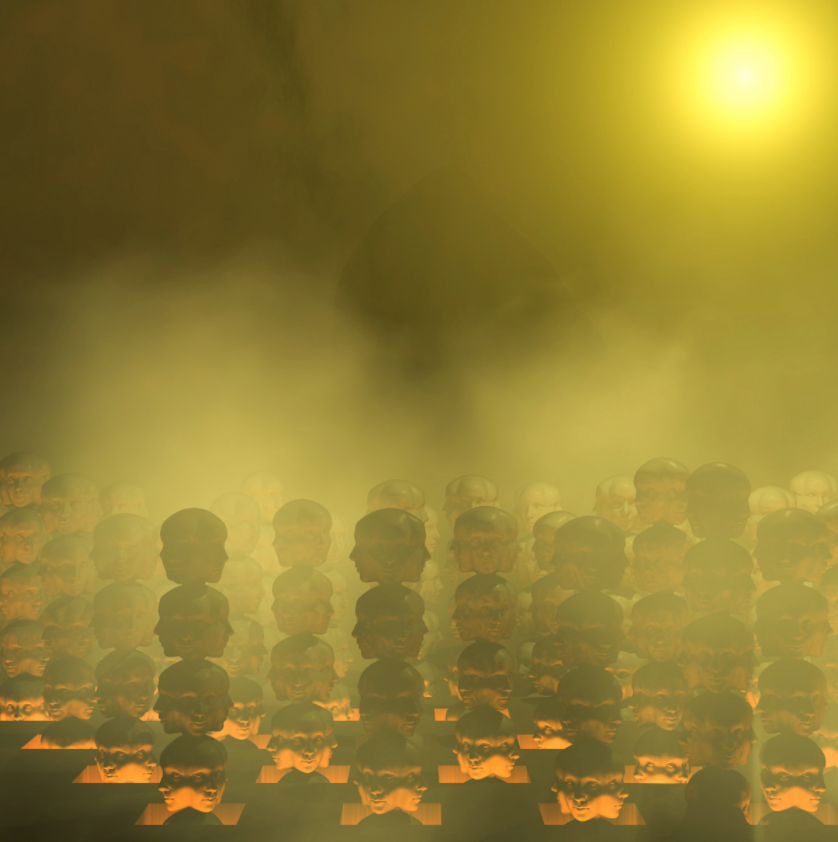

It was in 2011 in Papua New Guinea that Payes’ ecological concern was first stoked. This newfound anxiety about human-induced climate change became palpable in her images, effortlessly fusing with and enriching originary themes of transformation and flux. Disorienting and powerfully enigmatic, Sulphur Rising, Geyser 6 and Vapour 2 (2017) present unsettled, primordial landscapes full of violent, elemental forces. Meanwhile – combining analogue and digital approaches – sulfurous yellow contaminates watery pools of blue in her 3D Icescape 12 (2011), highlighting the toxic overexploitation of the environment by humanity.

The imagery of Interzone #10 (2013), then, is characteristic of Payes’ attitude of optimism. Arising from the earth bathed in a diffuse fiery glow, columns of heads with four faces – digital avatars of her daughter Ilana – emerge to re-populate the barren landscape. Even in the most inhospitable terrain, Payes’ insists, nature adapts and life somehow persists.

Stephen Dupont - Fire, 2020 inkjet prints 101 x 152 cm

The catastrophic fire season in Australia this year began in mid 2019 and more than 240 days and 46 million acres of burnt land later, the inferno was still blazing. The ‘Black Summer’ of 2019/20 was the most disastrous fire season the country had ever seen: 34 people died, 5,900 homes were destroyed, and an estimated one billion animals perished, with some endangered species now extinct. The fires were eight times larger than the 2018 California fires and smoke from the blaze obscured the skies around the world. NASA tracked a plume of smoke from Australia that was the size of the United States, and found that it had circumnavigated the globe, returning to eastern Australia.

Confirming what we already expected, scientists have said that global warming increased the risk of the hot, dry weather that causes bushfires by at least 30%. As the climate becomes more variable and more severe, Australians are getting a glimpse at its potentially dystopian future of worsening droughts and fires. In January 2020, millions of Australians turned their collective grief into action and rallied against the governments’ passivity on the issue of climate change, piling political pressure on leaders to take bolder action and to help make sure these horrors are never repeated.

Kurt Sorensen - Port of Call, 2012 silver gelatin prints made from wet plate collodion negatives 43 x 53 cm

Combining history and anthropology, Kurt Sorensen’s photographic practice echoes a colonial history, invoking the antagonistic encounter between early European settlers and the Australian landscape. A Gothic consciousness emerges in his images: a wilderness pulsating with unseen forces, obscured by clinging mist or undulating shadows; a brutal past lightly ghosting the surface of the present.

Port of Call (2012) might be his only portrait-based series, but it maintains a characteristic communion with recent history. It harks back to 1788 and the cargo of the First Fleet, comprised of 736 convicts and some British troops, who went on to establish the first colony of New South Wales at Sydney Cove. A working-class community soon developed, and its residents came to refer to the area as ‘The Rocks’.

Sorensen’s portraits depict the contemporary descendants of these originary settlers. Utilising the technique of wet collodion printing common in the 19th century, his subjects gaze out at us from a monochrome limbo. Saturated in shadow and merging against an ageless interior, these haunting figures channel Australia’s dank, dark history of colonialism and incarceration.

Torika Bolatagici - Ecology/Economy, 2013. Vocals by Joseph Chetty video

Fijian military bodies have become a valuable commodity in the economy of war. Bolatagici’s research is concerned with the ways the Fijian military body has been mythologised and constructed through colonial and neo-colonial representations. She is interested in Fijian agency, and the ways Fijian masculinity is performed in vernacular contexts. Ecology/Economy speaks simultaneously to Fijian bodily practices and through indigenous ways of knowing through the body, while linking indigenous embodiment to broader somaesthetic narratives of corporeality and the geographic movement of bodies transnationally - what Joseph Pugliese calls ‘geocorpographies’ and the commodification of Oceanic bodies within the contemporary military complex. In this work we see the cycle of life played out on the Fijian ibe (woven mat) which holds ceremonial importance in Fiji at various stages of the life cycle, from birth to death. In Ecology/Economy we see the child’s health and wellbeing being nurtured by a loving father through massage. At the midpoint of the work, the screen splits to address the notion of Fijians dying for foreign armies abroad. The soundtrack is a Fijian lullaby about going fishing, which ties in notions of village sustenance and local economies.

Angela Tiatia - Interference, 2018 video

Representation, gender, decolonization, and climate change: these themes all coalesce in Angela Tiatia’s artistic practice. She employs installation, performance art, and digital video to incisively dissect the cultural norms of both the Western world and the colonised Pacific.

Reminiscent of the ocular overload and rapid-fire editing of MTV, her short video work Interference (2018) begins with the promise of transcendence. Three performers move uninhibited across a pitch-black screen, a negative digital effect obscuring their identity. But this unified visual field soon cedes to a modulated blitzkrieg of imagery accompanied by a pulsing soundtrack. In under thirty seconds, the viewer is assaulted by a variety of representations that encompass art history, anthropology, science, fashion, and popular culture.

Here Tiatia concisely evokes a process of psychic colonization; an onslaught of external influences that problematize individual self-actualization.

Silvi Glattauer - From Bitangabee to Arenys du Munt, 2015 photogravures with Japanese Gampi paper 50 x 50 cm

Nature and narrative are central to Silvi Glattauer’s output. She combines multiple photographic techniques and a handmade aesthetic to create images that render time, place, and beauty palpable. In the process, her work invokes notions of materiality, object, and preciousness.

As part of her “Objective Archives” series, which uses found objects and national parks as inspiration for storyboards of time and place, Glattauer took images of Bittangabee Bay in New South Wales. From Bittangabee Bay to Arenys Du Munt (2015) charts the works’ journey as they became intricate photogravure prints in Catalonia, Spain, further embellished with jade Japanese Gampi paper.

Glattauer’s handmade methodology extends conventional ideas of photography as mechanical reproduction: crafting unique pieces whose sculptural, three-dimensional qualities enchant the sense of touch as well as sight.

Katrin Koenning - Three from Lake Mountain, 2018 inkjet prints 80 x 100 cm

Summer is always a high-risk season for fires in Australia, with drought and high winds commonplace. But in the summer of 2009, the conditions worsened and it became a season of sorrow with the Black Saturday bushfires at Lake Mountain, a popular winter destination and ski resort in Victoria, Australia. The weather conditions that week were poor: extremely low humidity of two percent, the bush was tinder-dry, winds of 62 mph were expected and the hottest temperatures ever were recorded at 115 degrees Fahrenheit. Authorities went on to tell the public that February 7th would be the worst day of fire conditions in the history of the state and that would create the perfect firestorm. On the day of the fire, high winds knocked down a power cable which sparked a bushfire that resulted in the country’s highest-ever loss of human life from a fire: a total of 173 people were confirmed to have died.

Katrin Koenning has an ongoing interest in this site at Lake Mountain, returning, again and again, to bear witness, documenting the effects of climate change and aftermath of the fires for the last 10 years. At first glance, this image in this triptych appears to be covered in ash, but this photo was taken years after the fires and is of a winter scene, depicting trees blanketed with snow. There is a certain stillness to the photos that should give everyone reason to pause; they show an environment struggling to regenerate, a tragedy which asks us to recognize that, because of climate change, we might be indirectly responsible. Each of Koenning’s photos from this series has a personal significance, which is intimated but never fully revealed and which is part of an emotional and intellectual journey.

Kate Robertson - Recording the medicinal plants of the Siwai, Bouganville, 2016 rag paper prints various sizes

Working closely with communities whose lifestyles are in harmony with the natural world, Kate Robertson uses analogue and digital photographic techniques to translate the imperceptible phenomena of healing into a visual language; creating images that embody a sense of the numinous.

Concerned that the gradual obsolescence of traditional knowledge was being hastened by global technologies, Chief Alex Dawia of Taa Lupumoiku Clan invited Robertson to document the medicinal plants of the Siwai region, Bouganville, insisting that “you have the tools, and we have the knowledge. Together we can make something unique.” The project would serve numerous ends: disseminating forgotten knowledge among the community and recording it for posterity; preserving the Motuna language integral to understanding the plant’s medicinal applications; and offering a positive instance of a place recently recovered from civil war.

Opting for a camera-less approach, the community, environment, and Robertson act as co-authors of the resulting photograms. As the organic plant matter reacts to the chemicals in the photographic paper – whose effects alter dependent on weather conditions – the images become singular expressions of the plants’ innate qualities, and turn various pastel hues of brown, pink and yellow. Robertson’s pièce de résistance, however, is to rend the work from the scanner as it’s digitized: the final pixelated, glitchy image intimating the precarious status of all forms of knowledge.

Jane Brown - Australian Gothic, 2011 silver gelatin prints 17 x 21 cm

“The antipodes was seen as a world of reversals, the dark subconscious of Britain. It was for all intents and purposes Gothic par excellence.” –Turcotte, Gary, “Australian Gothic”, in Mulvey Roberts, M (ed.), The Handbook to Gothic Literature, Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1998.

Comprising photographs taken in rural New South Wales, the ACT, Victoria, and Tasmania, this work takes its cue from the gothic imaginings of colonial Australia. We see images of a convict past, the bush Christmas, unforgiving landscapes and melancholic hotels. It carries echoes of the cinema of Wake in Fright (1971) and the Cars that Ate Paris (1974).

Rendering visible the themes of the melancholic and the uncanny, Australian Gothic manifests itself in rural isolation – where the homely becomes unhomely (or unheimlich) and where nature is out of kilter.

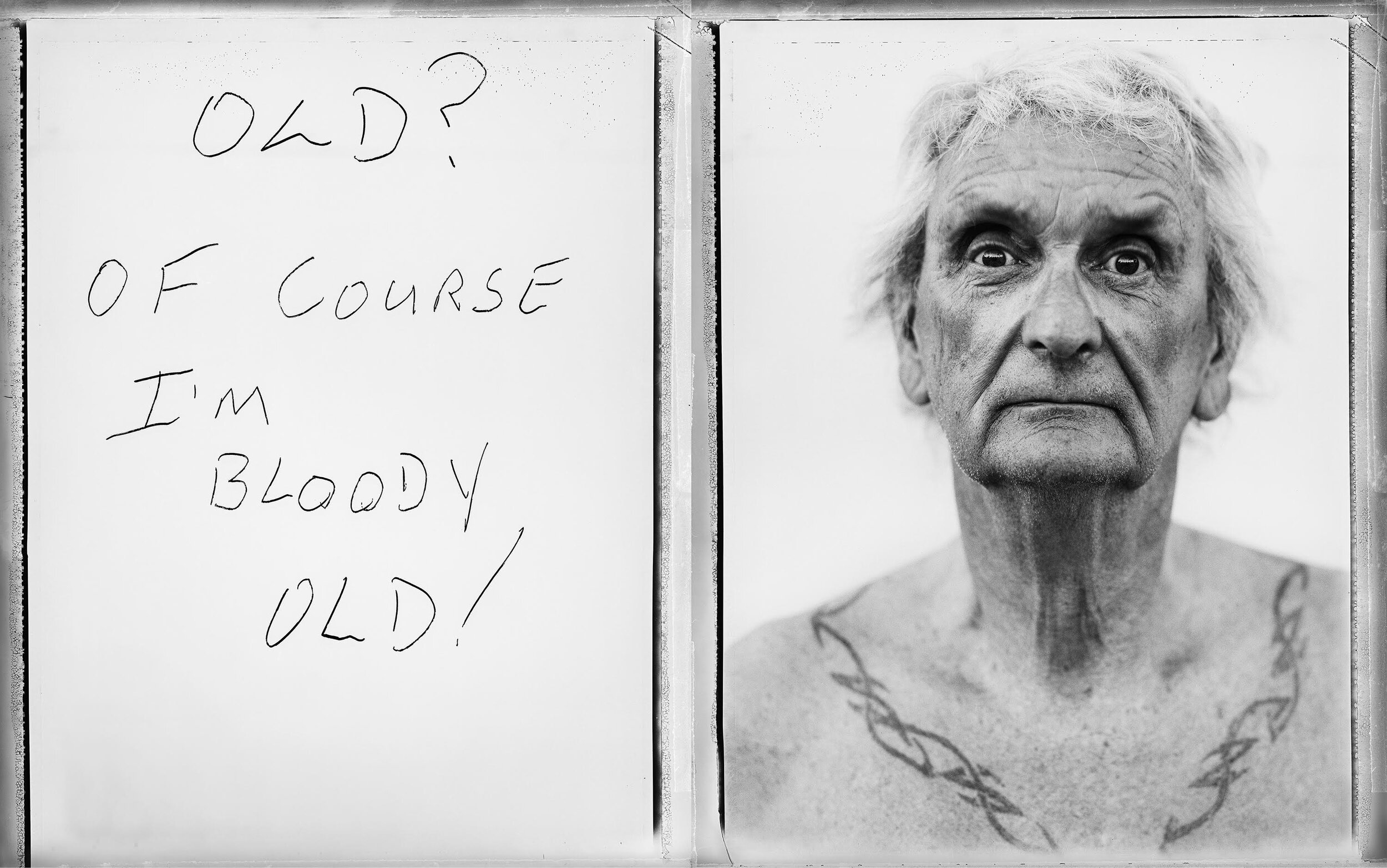

Tobias Titz chromogenic prints 50 x 76 cm

“How come we had to become a citizen of our own country? We were here first!” These words from a young Indigenous Australian sit alongside their Polaroid portrait, an indignant comment on Australia’s 1967 referendum. It’s one of many diptychs by Tobias Titz, whose Polaroid Project has provided Indigenous Australians, immigrants and refugees with both a voice and visual representation.

His co-authored images marry ethics and aesthetics. After taking his sitter’s portrait, the subject leaves the shot and another picture is taken of the vacant scene. They’re then invited to convey their subjectivity through the empty negative: thoughts, feelings, and drawings being scribed into the wet emulsion. Rather than imposing his own artistic will, Titz creates a space for the subject to speak, resulting in singularly human portraits that challenge reductive stereotypes.

A variety of images from Right to be Counted (2007), Farewell 665 (1998-2020), and the Beyond Borders Project (2015) are included here: black and white images tinged with pathos, humour, and hope. The former, a collaboration with the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre, records the diverging opinions of Indigenous Australians about the 1967 referendum, a decision that gave them greater socio-political visibility within the commonwealth. Meanwhile, the title of Farewell 665 references the discontinued production of Polaroid film, with which Titz had captured – over 22 years and two continents – the lived experience of immigrants, Australians, and refugees.

Student Focus Section -

We recognize the devastating loss to this year’s art graduates so to accompany this exhibition we are pleased to present a display of work by Australian students and new graduates in the library of the Southeast Museum of Photography. Many of the artists were selected by artists in the main exhibition and their work can be seen here.

Artists: Igor Hill, Victoria Holessis, Georgia Jones, Aleksandar Matic, Kate Matthews, Natasha Narain, Manohar S Sidhu, Charlotte Tegan, Kiyan Zadeh