I Hear America Singing: Contemporary Photography from America اسمع امريكا تغني : تصوير فوتوغرافي معاصر من امريكا

See Arabic version here

Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts - Amman, Jordan October 20th - November 25th, 2021

Matthew Brandt, Mercedes Dorame, Lucas Foglia, Wen-Hang Lin, Michael Lundgren, Alex Maclean, Griselda San Martin, Pamela Pecchio, David Benjamin Sherry, Xaviera Simmons, For Freedoms, Greg Stimac, Millee Tibbs, Wendel White, William Wilson

Who constitutes America? For the great 19th-century poet Walt Whitman, America was the totality of its people working in concert, each providing their own individual and equally valuable contribution to the nation. First published in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, “I Hear America Singing” celebrated America’s vibrant multiplicity: depicting a nation in rude health whose collective strength derived from the “varied carols” of its citizens. His poetry exalted the democratic ideals of the U.S Declaration of Independence and the natural equality of all human beings.

Whitman’s literary idyll of national unity, penned just before the outbreak of the Civil War, has proven rather fallacious by the standard of American history, with myriad communities denied the “inalienable rights” of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence – for example, the country’s Indigenous population. The Langston Hughes poem I, Too, written in 1925, attested to the discrimination faced by African Americans in the age of Jim Crow, while Martin Luther King stressed the need “to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood” as thousands marched on Washington in 1963 to demand racial equality.

The first exhibition of American photography to take place in Amman, Jordan, I Hear America Singing: Contemporary Photography from America deconstructs a singular notion of national identity to convey the United States’ kaleidoscopic diversity. Through a combination of digital, analogue, conceptual and archival approaches, the sixteen photographers exhibited here offer a collective rebuke to a foundational legacy of white male cultural hegemony. By acutely interrogating the nuanced landscape of American identity and its ideological elisions, their work helps to broaden the lexicon of the country’s visual culture and the people it represents.

The exhibition is divided into three main parts – Landscape, Portraiture, and American History. The stunning large-scale images of aerial photographer Alex Maclean, taken from his Agriculture (2016) and Arid Lands (2009) series, demonstrate a tension between civilization and nature. Their bold colors and geometric forms beguile, but equally signify an environment denuded by anthropogenic activity. Millee Tibbs and David Benjamin Sherry explore a similar dialectic, with their aesthetic methodologies both embellishing and disfiguring the environment they represent. In Mountains + Valleys (2013), Tibbs critiques the genre of landscape photography by physically manipulating her work using the principles of origami, an act that draws analogy to the ideological distortions inherent in imagery that purportedly represents an objective reality. Sherry’s monochromatic images of the American West in American Monuments (2019), meanwhile, employ a striking use of saturated color to suggest a natural world out of balance. But they also “queer” the reception of the traditional landscape photograph: their vivid, expressive quality opening each image up to a plurality of interpretations beyond the strictly masculinist, and investing them with animistic life.

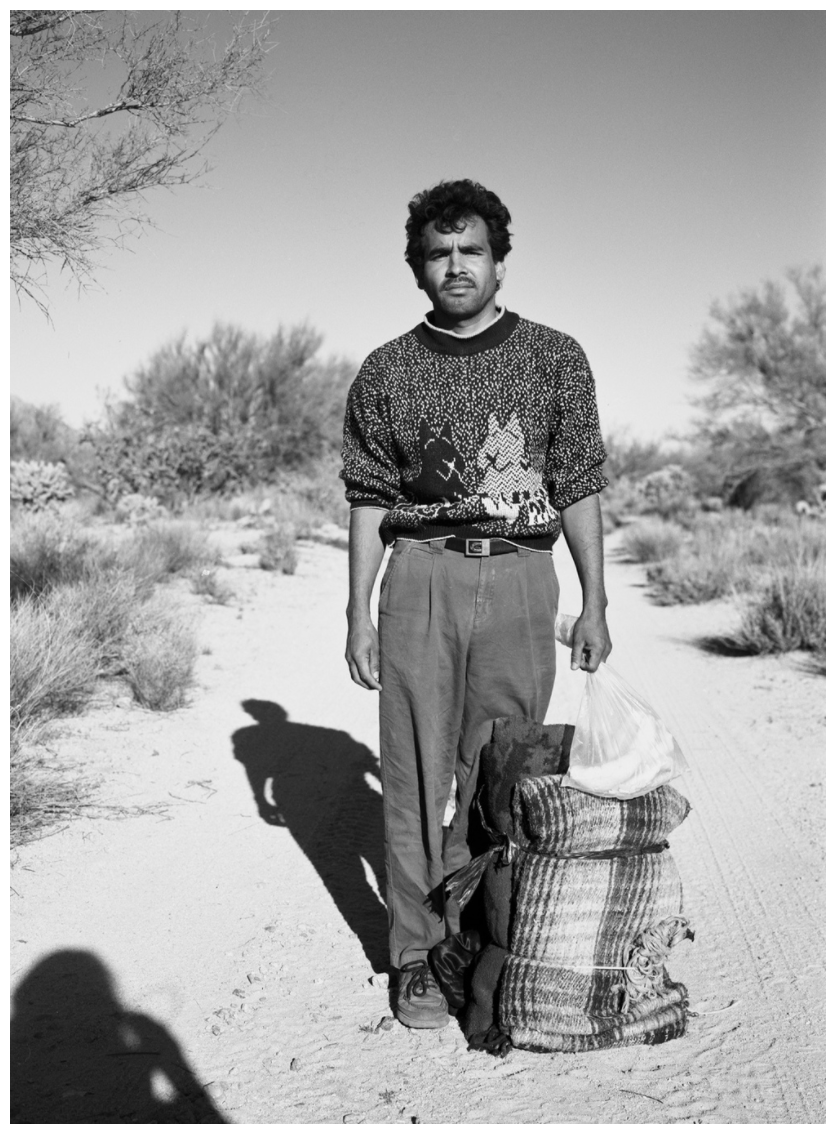

Lucas Foglia’s Frontcountry (2006-2013) is a contemporary account of rural America, ranging from the Mountain State of Montana in the north to Texas in America’s South Central region. There’s a feeling of community, purpose, and action in images of ranchers training horses to herd cattle, or of young men poised to receive an incoming football against Wyoming’s snow-capped mountains. His work transcends clichéd representations to document the breadth of people that populate this rapidly transforming landscape, from female haul truck drivers to cowboys from Central and South America. Yet he also lucidly conveys the ongoing industrial transformation of once-pristine wildernesses for financial gain. Complementing Foglia’s series are a variety of Michael Lundgren’s black and white portraits, taken between 1998 and 2012, of individuals photographed among the huge spaces and rugged terrain of the American West. There’s something uncanny about these ostensibly ordinary shots: pervaded by a diffuse sense of perpetual twilight, and whose human subjects often appear like extensions of their surroundings. J.S. Anderson writes of Lundgren’s work that it “capture[s] the numinal in the phenomena of the desert landscape”, and it’s this quality that evokes a sense of communion between mankind and an aeons old natural world.

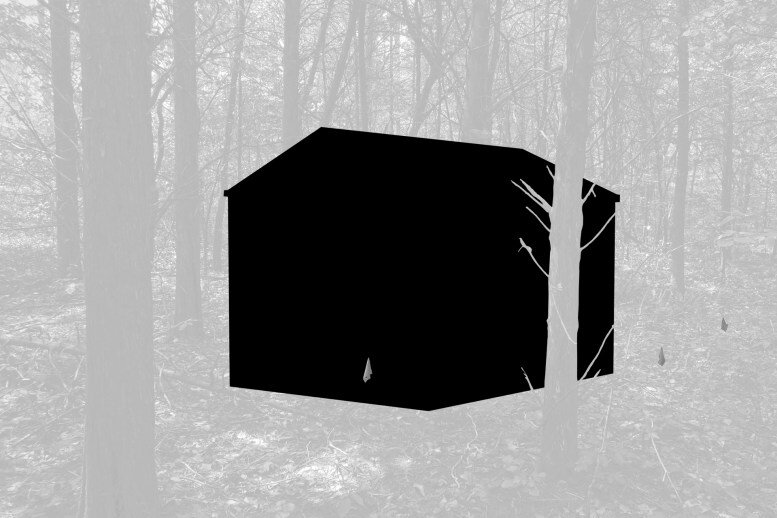

As Wendel White and Griselda San Martin’s projects illustrate, the landscape – particularly the architectural features embedded within it – can be appropriated to reinforce a narrow idea of American identity while also physically excluding those it deems culturally ‘other’. White’s project Schools for the Colored (2002-2010) documents locations and buildings in Northeastern states like New Jersey that once functioned as segregated schools. In the artist’s digitally-edited images, the locales adjacent to the Black-only schools are ‘screened out’ to convey African Americans’ enforced separation from white society and a history of “educational apartheid”. Meanwhile, Griselda San Martin’s The Wall (2018) depicts an ongoing method of exclusion: the border wall that extends 1,933 miles between the United States and Mexico to prevent immigrants from entering America. Yet, in focusing on the interactions at Friendship Park, where Mexican families from both sides of the border can meet – although separated by a colossal metal fence – she humanizes individuals who daily receive the message that they’re not welcome in America.

Despite a narrative of Americanness that disavows difference, the nation’s varied racial and ethnic makeup has been integral to its development, culture, and growth. Historian Hampton Sides has described the United States as “a glorious mess of contradiction, such a crazy quilt of competing themes, […] a fecund mishmash of people and ideas”. This cultural plurality is evident in the work of For Freedoms (Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur), Mercedes Dorame and William Wilson, Wen-Hang Lin and Xaviera Simmons, manifested through their divergent approaches to portraiture.

While Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms extolled America’s democratic ideals in 1943 as fascism spread through Europe, his illustrations offered only a monocultural representation of the American people. As conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas explains, “at that time in America, it seems what it meant to be American was white Anglo-Saxon”. Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur collaborated with Eric Gottesman and Wyatt Gallery of For Freedoms to create Four Freedoms (2018) which re-staged Rockwell’s original four images – Freedom from Want, Freedom from Fear, Freedom of Worship, and Freedom of Speech – but with a cast of actors more accurately reflecting the USA’s racial, religious, and ethnic composition.

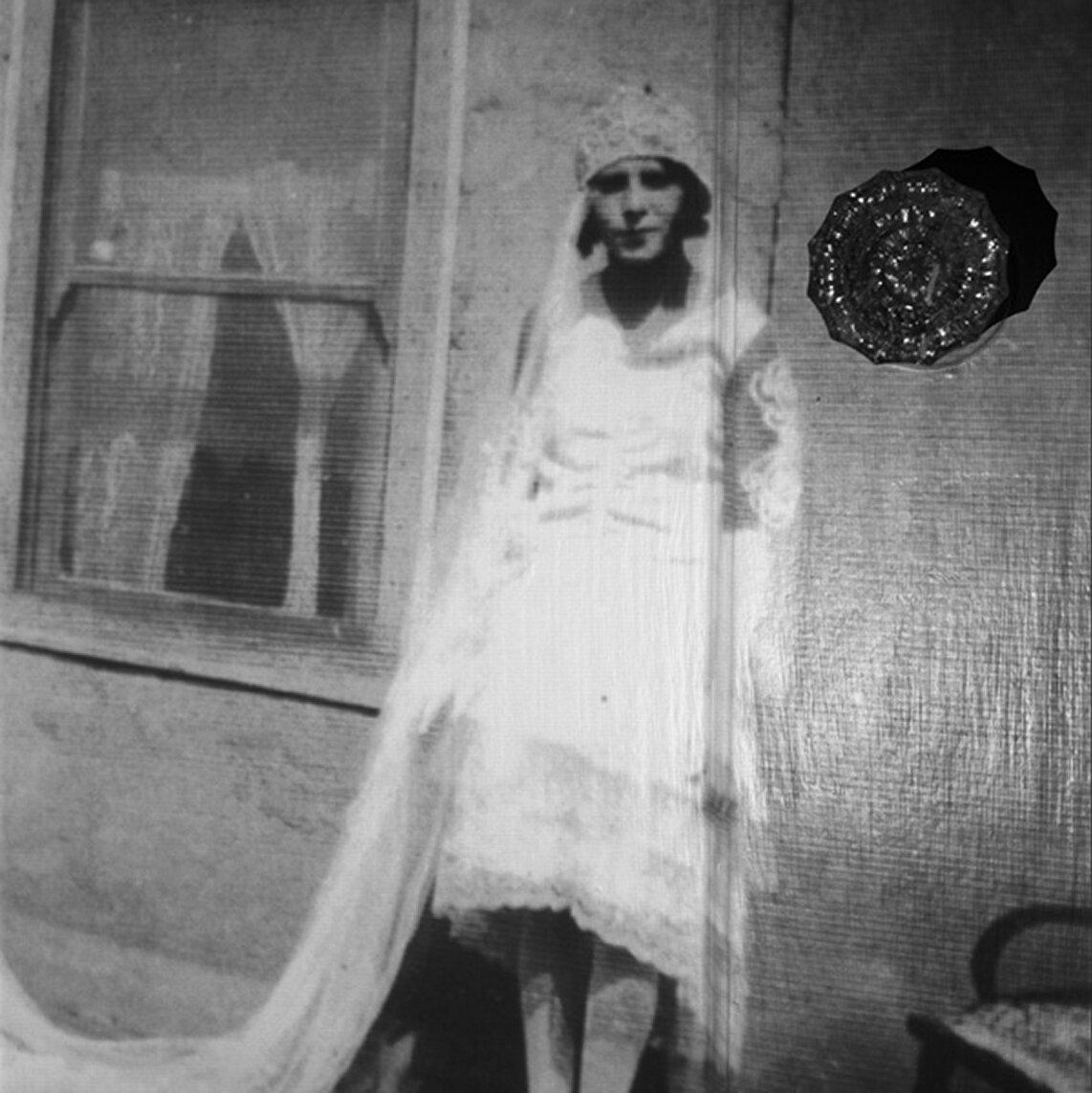

The country’s Indigenous populations find increased visibility in the work of Gabrielino-Tongva artist Mercedes Dorame and Diné photographer William Wilson. In each, the legacy of a subjugated past is brought to vibrant life in the present, demonstrating the continued existence of Indigenous culture in America. For Living Proof (2010), Dorame projected old family images around her Los Angeles apartment: granting her relatives three-dimensional life among her living quarters, furniture, and effects. In a similar vein, but utilizing two different media, Wilson’s Talking Tintypes (2015) employed the Wet Plate Collodion process to render his subjects with a 19th-century aesthetic, and simultaneously filmed them as they discussed their ancestral history and culture. In the exhibition, viewers can bring his photographs to audio-visual life with the Augmented Reality app Talking Tintypes, by pointing their smartphone at each image and engendering a kind of revisionist magic. Reconciling two realities – the richness of Indigenous culture and the colonial oppression of the past – the series bestows Indigenous people with an agency historically denied.

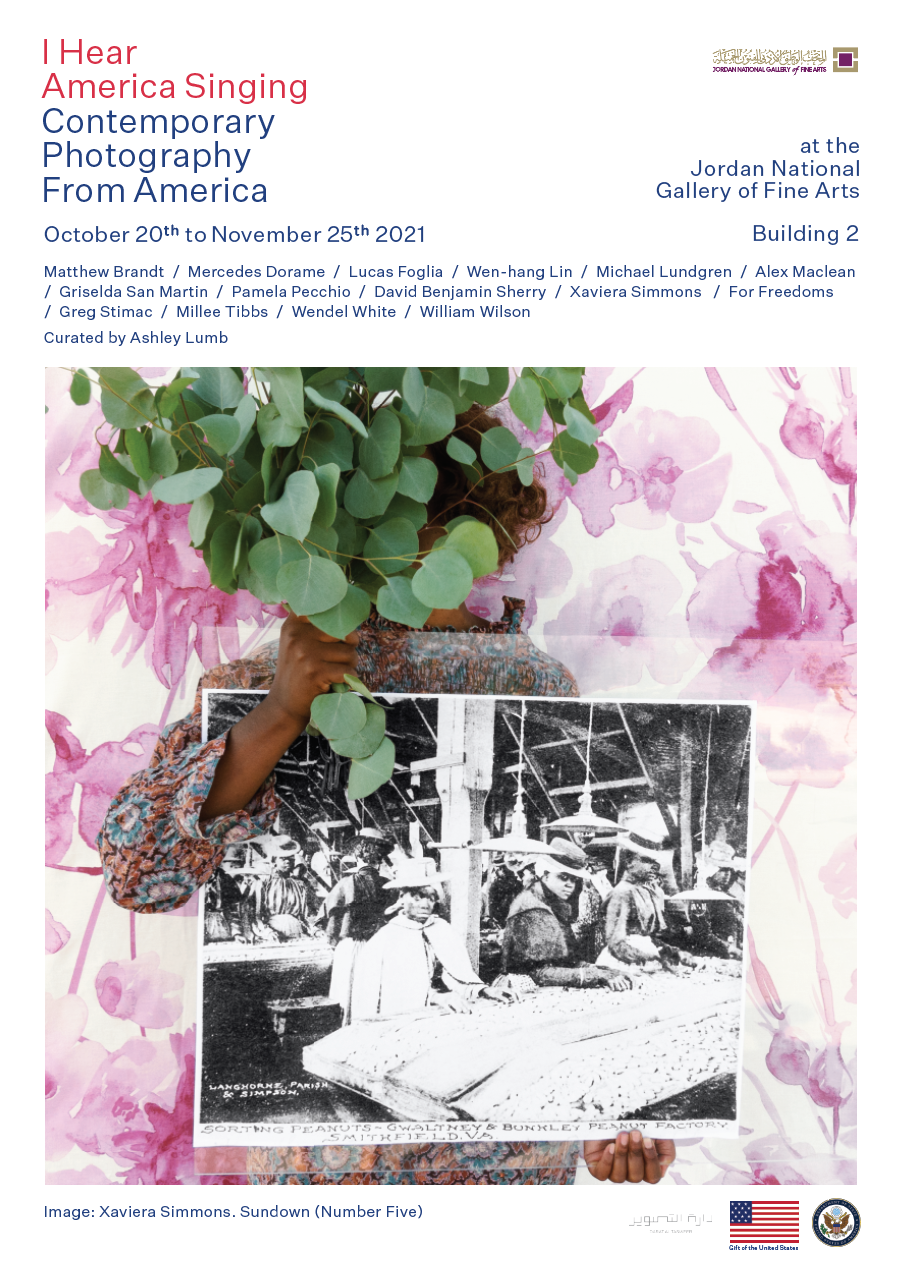

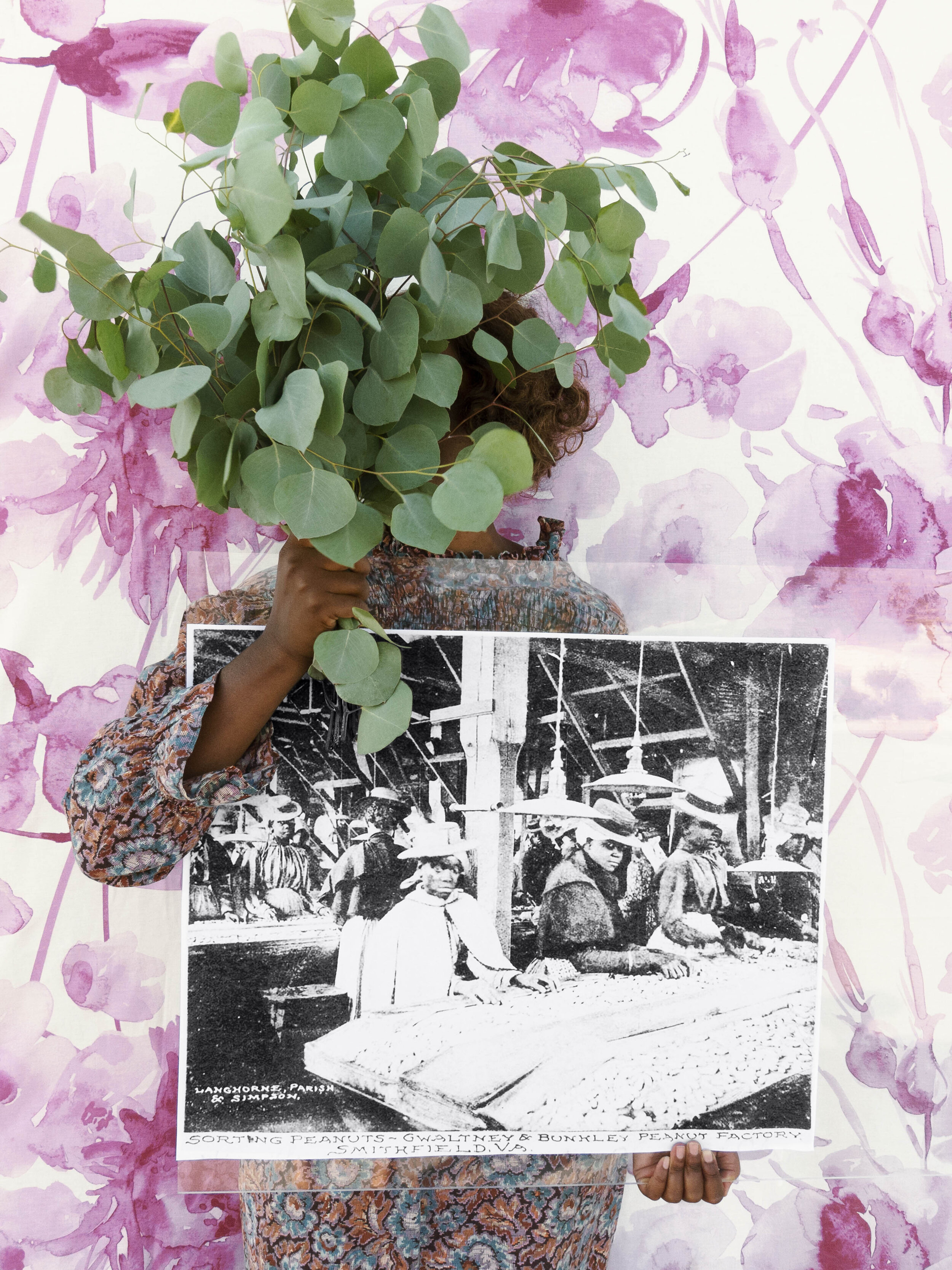

The complex and multi-faceted nature of identity is an integral part of two ongoing projects by Xaviera Simmons and Wen-Hang Lin. In Simmons’s Sundown (2018 – ), whose title invokes the all-white neighborhoods where Black descendants of American slavery were prohibited from being after dark, a woman holds up a variety of archive images: snapshots from the age of Reconstruction, segregation, and chattel slavery. They provide a dramatic contrast with background screens of colorful fabric covered in lilac flowers, and the woman’s patterned floral attire. In each image her face is masked – subsumed among a “landscape of identity” – so that the series posits individual identity as itself highly plural, intimately linked with familial lineage and our natural and cultural environments. Lin’s And I Wander (2019 – ) is also dreamily subjective, functioning as a “metaphorical self-portrait” of the Taiwan-born artist, who’s lived in America for 30 years now. Each shot sees Lin position a mirror – cut to form his own silhouette – in different locations throughout the Arizona wilderness. Among the shifting landscapes, the artist’s reflective-surrogate blends in with varying degrees of efficacy, woozily echoing the native flora, desert earth, and clear blue sky. And I Wander powerfully articulates a desire to belong in a foreign culture, and the complex and ongoing negotiation of it with one’s originary identity: a tension explored through visual dialectics of absence and presence, assimilation and difference.

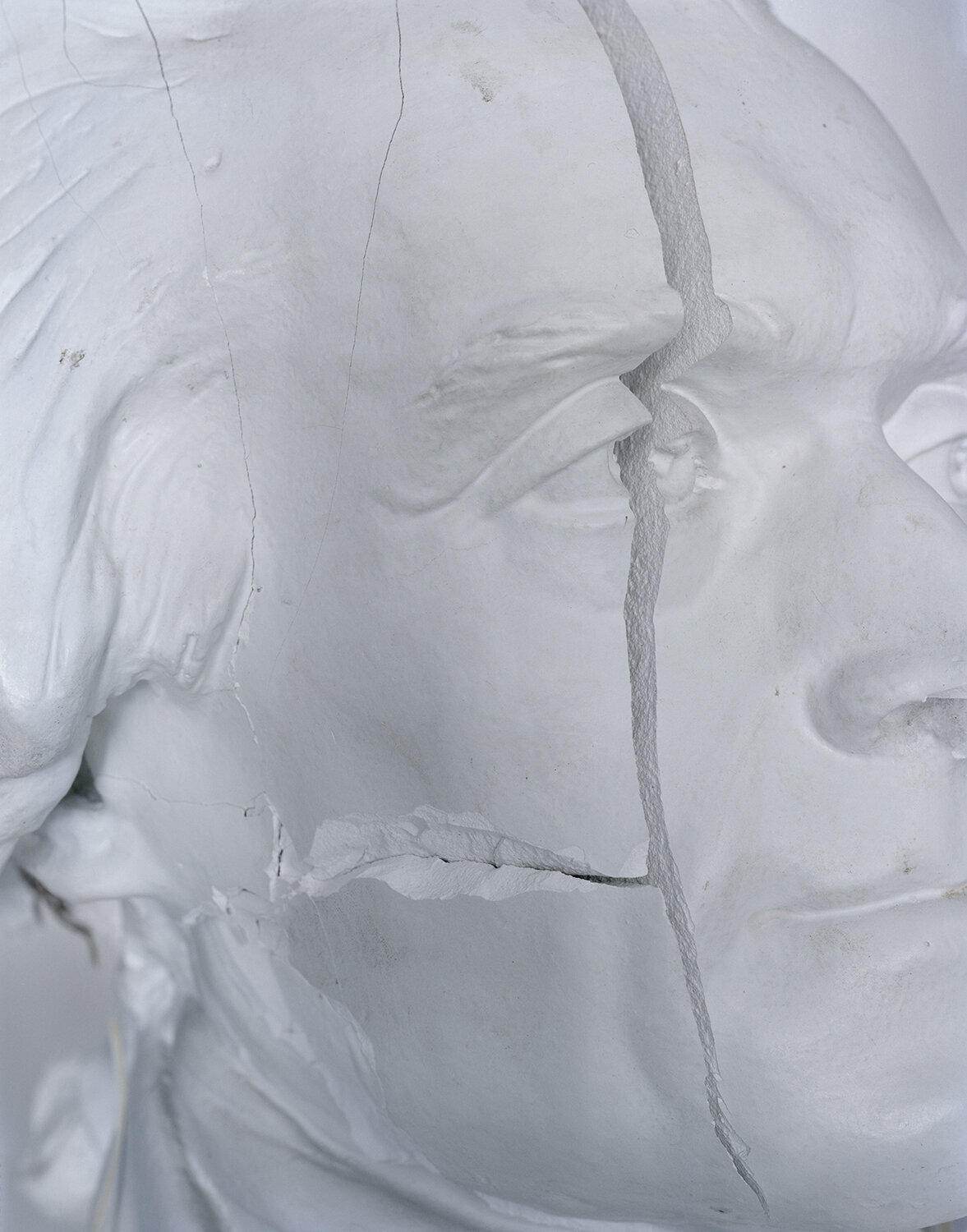

While much of the work here engages with national history, Matthew Brandt, Pamela Pecchio, and Greg Stimac explicitly mine major political and cultural symbols to critique an inherited, hegemonic idea of what it means to be American. In doing so, they explode a monolithic narrative of American history to make way for plural truths and realities.

When first exhibited at The Newark Museum, New Jersey, between 2019 and 2020, Matthew Brandt’s daguerreotypes of battling bald eagles held up a mirror to the contentious state of government under Donald Trump. Yet the work also illuminates a foundational dichotomy at the heart of American identity. Based on images taken in Alaska in 2014, and made using Fine Silver United States Liberty coins melted down, they highlight the shadow side of an American icon. Picked to represent the newly found nation in 1789, the bald eagle was lauded for its “fierce beauty and proud independence” by John F. Kennedy, but considered “a bird of bad moral character” by Founding Father Benjamin Franklin. In depicting them with a 19th-century photographic technique, and using Liberty Coins bearing the proud stamp of this natural predator, we’re reminded of the correlation between America’s ideals of freedom and strength, and a historical reality of violent domination over the land and its native people.

Likewise, Pamela Pecchio keenly interrogates the mythological status of American icons. In her series Founder (2017 – 2021), the artist created and photographed still lifes and collages made from ephemera indicative of American history. Four images are included here, each one based on an American president: George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. Through the juxtaposition of various materials – for example, Washington’s false teeth and paper wisteria culled from Mount Vernon – Pecchio destabilizes these figures unimpeachable legacies and encourages their re-evaluation.

Greg Stimac’s practice regularly returns to symbolic items and rituals charged with an explicitly American sensibility. His Golden Spike (2012) indicates an experimental approach to imaging the ‘last spike’, made to commemorate the joining of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads that formed the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. A revered artefact frequently photographed by visitors to the Cantor Arts Center in Stanford, California, Stimac’s photogram goes beyond appearances and attempts to elucidate the item’s national and socio-historical significance. The completed photogram, made by placing the object on silver gelatin paper and exposing it to light, renders the spike as a ghostly trace outlined by silver monochrome. The excision of its image fosters a perceptual shift from its material reality to something more conceptual: inviting the viewer to contemplate the interplay of absence and presence in the context of American history. What was sacrificed to complete the railroad and fulfill America’s expansionist project of Manifest Destiny? This non-representational image-void encourages us to call forth the narratives and histories that aren’t reflected in the Golden Spike’s gleaming façade: legacies of colonialism, genocide, racism, and environmental degradation.

“Of every hue and caste am I, of every rank and religion”, Whitman wrote in “Song of Myself”. It’s a sentiment that embodies the American nation, vibrantly echoed in the work of the sixteen photographers here and reminding us that the American landscape has always been a place of cultural plurality and difference. Various ideologies may have tried to elide this multiculturalism. But, from the vantage point of 2021, we hear America singing louder each day, ever more determined to realize what Langston Hughes termed the “mighty daring” of its founding ideals: of equality, democracy, and justice for all.

*This exhibition is funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

Matthew Brandt - Rocks and Eagles, 2017 - 2019 Daguerreotype made from American Silver Eagle coins and glass, 10 x 8 x 1 inches

In Rocks and Eagles, Matthew Brandt created a series of daguerreotypes of American eagles, made from Fine Silver United States Liberty coins and silver ingots manufactured by the Newark metal refinery Engelhard Industries, melted down to create daguerreotypes. Inspired by the recent political atmosphere, these photographs, originally shot in Alaska in 2014, depict bald eagles fighting for salmon.

William Wilson - Talking Tintypes archival pigment prints, 22 x 17 inches

William Wilson is a Diné photographer who spent his formative years living in the Navajo Nation. In this series, Wilson uses an old fashioned, large format camera and the historic wet plate collodion process. As a gesture of reciprocity Wilson gives the sitter the tintype photograph produced during their exchange with the caveat that he be granted a non-exclusive right to create and use a high-resolution scan of their image for his own artistic purposes. This critical indigenous photographic exchange generates new forms of authority and autonomy. These alone, rather than the old paradigm of assimilation, can form the basis for a re-imagined vision of who we are as Native people.

In his Talking Tintype series, Wilson combines video and still photography to create a hybrid art form, marrying a 19th-century photographic process with 21st-century augmented reality. "I make a still image, the tintype, and at the same time we have a video camera rolling," he says. "I've developed an app, a free download on the app store called 'Talking Tintypes,' and it enables you to link the two." (download the app Talking Tintypes and point your phone towards the photo on your screen to see the photo play)

Mercedes Dorame - Living Proof, 2010 archival pigment prints, 24 x 24 inches

Mercedes Dorame tries to move people beyond ‘You don’t look Native’. A CD filled with old family images led Gabrielino-Tongva artist Mercedes Dorame on a journey to bring them into her day-to-day environment. She placed the images around her Los Angeles apartment and photographed each composition. Dorame says that the portfolio, which she calls “Living Proof” is part of an effort to shed light on the survival of her tribe’s culture through a history of violence and forced assimilation toward Native Americans in this country. She said her grandparents rarely spoke of being Native American until later in their lives.

“It’s really hard to acknowledge the gaps in your own history,” Dorame said. “It’s hard to acknowledge that there are these kind of holes and places that you don’t know how to fill it in.” She hopes to interest others in her tribe—in the past and the present—with her work. “So much of what I want my work to do is bring visibility back,” she told PBS. “I want people to know that we as a tribe, we as a people, still exist.”

According to the tribe’s website, the Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe is a California Indian tribe historically known as the San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians. The tribe is not one of the many federally recognized tribes in California, which means they don’t have any reservation land or access to federal funding. “I think that because we don’t have reservation land, we’re kind of a splintered group. There’s been a lot of contention. And I really think it’s because there is no central place to have ceremony. There’s no central place to remember. There’s no central place to bury our dead,” Dorame said.

Pamela Pecchio - Founder

George Washington’s Teeth, 2021 Madison #1, 2021 Adams #1, 2017 Father (Jefferson), 2017 pigment print, 20 x 16 inches

The definition of founder that resonates most for Pamela Pecchio is its use as a verb. To found is to “come to grief, to fail, to sink, to become submerged, to send to the bottom, or to collapse.” American history, as most histories, is in a repetitive loop.

Pecchio became interested in the US Founding Fathers while living in Charlottesville, where Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia. Founder began as a response to traces of the Founding Fathers that marked the local landscape. Since her relocation to Boston, she has continued this work in the birthplace of the American Revolution. Both cities have seen war and civil unrest, Charlottesville taking the national spotlight in 2017 when a white supremacist drove his car through a group of counter-protestors.

“My studio contains books, scraps of paper, vegetation, wallpaper samples, postcards, and other memorabilia and ephemera that reference American history. I spend my time cutting and placing things together to see what happens. After I construct still- lifes and collages, I photograph them with a view camera. I am interested in the relationship between history and mythology, and conceptual parallels between the collage of materials, and the collage of stories that become history.”

Wendel White - Schools for the Colored

Brooklyn, IL, 2003 Future City, IL, 2008 pigment inkjet on paper, 18 x 24 inches

Schools for the Colored is an extension of the ideas that formed the project Small Towns, Black Lives, in that, it is a continuation of Wendel’s journey through the African American landscape. He began making photographs of historically African American school buildings during the very first weeks of the Small Towns, Black Lives project more than twenty years ago. In Schools for the Colored he began to pay attention to the many structures and sites (also making photographs of places where segregated schools once stood) that operated as segregated schools.

The architecture and geography of America’s educational apartheid, in the form of a system of “colored schools,” within the landscape of southern New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois is the central concern of this project.

Xaviera Simmons - Sundown (2018 - ongoing)

Sundown (Number Fourteen), 46 x 37.5 inches Sundown (Number Five), 60 x 45 inches chromogenic prints

Xaviera Simmons’s Sundown series (2018– ongoing), is an encyclopedic exploration of contemporary American life as shaped by the legacies of slavery, colonialism, segregation, and migration. The series draws its name from so-called sundown towns—places known to be unsafe, especially at night, for black people—and is shaped by her archival study of records of life in the Jim Crow era.

The woman in the photo holds a mask of indeterminate origin over her face, suggesting a form of mediated looking—perhaps revealing views of the slave trade’s legacy and new visions for the future—and referencing the mask’s currency as a collectable signifier of the Western idea of Africa, sold and traded as a commodity. Through such performative staging, Simmons’s work embeds heavy visual metaphors within a lush aesthetic to point to the still-precarious circumstances of people of color in America. What strikes the viewer is the amount of light that’s found in Simmons’ work. While depicting a dark history, the re-contextualized images feature a beauty, a vibrancy, and a sense of hope.

Wen-Hang Lin - And I Wander, 2019 chromogenic print, 16 x 20 inches

Begun in 2018, And I Wander is an ongoing photographic series that acts as a visual metaphor for my struggle to assimilate into American life as an immigrant from Taiwan. It captures the vast, luminous landscapes of the Arizona desert, whose natural features – yawning blue skies and lush yellow and green flora – are dreamily reflected on the surface of a nebulous humanoid figure, which waxes and wanes in visibility between images: sometimes clearly differentiated against and occasionally hidden within its environment. Yet this chameleonic presence is never fully incorporated. Balancing the ‘yang’ of these landscapes’ tranquil stillness is the potent melancholy ‘yin’ of this solitary figure: conveying my unreconciled yearning for a sense of belonging in America.

Taking inspiration from the Hungarian artist André Kertész and his 1933 series of Distortion photographs, I cut out carnival mirrors to resemble my own silhouette and then place them within the landscape to function as my metaphorical surrogates. A figure is concealed to varying degrees within each image, depending on its relation to the camera and immediate environment. If foreground and background unite perfectly, visual continuity is maintained. It appears to merge with its surroundings; if not, this continuity is ruptured to surreal effect, making the hazy human form evident. While the figure’s rippling depth appears to be a digital effect, it’s entirely the result of my analog process. Taken on film using 6x7 and 6x12 medium format cameras, I simply focus the camera on the mirror’s uneven surface to engender this impression, which provides a visual analogy for my subjective experience.

Michael Lundgren - Portraits

Dutch Tourists in Death Valley, 1998 Don Hurd by the Salt River, 1998 Migrant below Baboquivari Peak, 1998 silver gelatin, 20 x 24 inches

For Freedoms (Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur in collaboration with Eric Gottesman and Wyatt Gallery of For Freedoms) - Four Freedoms, 2018

Freedom from Want Freedom from Fear Freedom of Speech Freedom of Worship archival pigment print, 52.5 x 42 inches

Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” series presented an image of America intended to bolster patriotic spirit during World War II. Based on a 1941 speech by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in which he extolled the global right to freedom of speech and worship, freedom from want, and the freedom from fear, Rockwell’s canvases were a celebration of Americana. It was, however, a selective celebration.

When Rockwell made these paintings in 1943, Japanese-Americans were imprisoned in internment camps while African-American soldiers who grew up under Jim Crow fought in segregated units. “At that time in America, it seems what it meant to be American was white Anglo-Saxon,” said the photographer and conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas. “We want to shine a light on the fact that artists’ work is often political and shapes culture and society.”

Using Rockwell’s paintings as a starting point, Thomas has reimagined the illustrator’s vision by recreating scenes that include faces that reflect this country’s complexity and diversity. Thomas — whose previous projects have examined race, commerce and advertising — enlisted the photographer Emily Shur to produce the works.

David Benjamin Sherry - American Monuments

Grand Plateau, Grand Staircase - Escalante National Monument, Utah, 2017 Joshua Tree, Gold Butte National Monument, Nevada, 2018 Newspaper Rock Petroglyph, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, 2017 Bears Earts, Bears Ears National Monumentt, 2018 chromogenic print, 40 x 50 inches

Using analogue photographic methods, David Benjamin Sherry reexamines the classic tradition of landscape of the American West. In his work American Monuments he presents photographs with vivid monochromatic palettes to shed light on the exploitation that threatens our country’s national monuments. Using 8×10 large format film, Sherry captures details and pristine qualities of the land. By pushing boundaries of darkroom techniques, he creates saturated monochromatic colors enticing the viewer into a world of alarming beauty. This transformation of the landscape offers a myriad of interpretations ranging from an immediate threat due to human impact to hope amidst environmental adversity. Sherry presents the viewer with an opportunity to contemplate the deep connections we have with our planet – what is seen on the surface verses what is hidden below. The viewer is left to contemplate where the truth lies.

Sherry says “Like many of my photographic forebears, I use an 8×10 large format film camera, which allows for an unrivaled level of detail. However, when printing, I’m not interested in depicting the way the subject appears in reality, but rather its potential for emotional resonance between viewer and subject. Color is a conduit for me to make those feelings visible. Like black-and-white photography, my monochrome, analog process foregrounds form, light, and composition, untethering the image from the constraints of straight representation. My aim is for the print to demonstrate my empathy toward the landscape and to help others better understand our physical and spiritual connection with the Earth. The color is emblematic of that intense connection, and yet simultaneously connotes my sense of otherness as a queer person. My travels have become a tool for processing the American queer experience as I navigate through rural spaces and communities stereotypically considered unsafe for queer people; queer narrativity is built into both the process and product of the work.”

Greg Stimac - Golden Spike, 2012 gold-toned silver gelatin print, 24 x 20 inches

Greg Stimac, a first-generation American artist, has long been reflecting on the ways that American life accrues its meaning, (it is large, and contains multitudes). The particularity of American life is often characterized by vague notions of freedom and open horizons, pure potentiality. Yet, in Stimac’s hands these ideas are shown to be dialectically related to the unnecessary frustrations, the violence and anxiety and absurdity, inherent to America. Waiting before the door-slab of the country, he concentrates on the question of what is involved in becoming American, and the opacity of what it means not to belong. And perhaps, Stimac seems to suggest, there is no ‘belonging’ to be had—at least not in any proper sense—save for those who don’t resist being determined by its terrible grip, those that name this land their own, mine and yours.

In Golden Spike, Stimac draws on subject matter that is quintessential of America ideals: the Golden Spike used to memorialize the completion of the first transcontinental railroad system in 1869. Deceptively simple, the work is a photogram of the Golden Spike made on silver gelatin paper. Stimac offers, with this, a testament to the way that even the simplest act of transformation of an image or object can suddenly render it otherwise. Exposed in this context, there emerges an alchemical dance, between iron (of railway nails), silver (of the paper), gold (of the spike). Together, the materials reveal a vacant, ghostly trace of the spike. The unassuming photographic print affords viewers a chance to reflect on the absence created by the presence of so-called American freedom, of the horizon we are promised but that we perpetually cannot cross. The railroad (and the spikes holding it down) is a suture binding the wound between the north and the south, still haunting us today; the gold of the nail, a distraction from the grim reality that is manifest destiny. Stimac’s work recognizes the way that techniques of apparently modest thinking can be deliberately used as a way of becoming sensitive—precisely by way of its simplicity—to the violence inherent to our everyday.

Lucas Foglia - Frontcountry, 2006-2013

Casey and Rowdy Horse Training, 71 Ranch, Deeth, Nevada, 2012 Jaime, Ranch Hand, Wells, Nevada, 2012 Amanda after a Birthday Party, Jackson, Wyoming, 2010 Produced Water, Hamilton Dome Oil Field, Owl Creek, Wyoming, 2013 archival pigment prints, 24.5 x 31 inches

Between 2006 and 2013, Lucas Foglia traveled throughout rural Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Wyoming, some of the least populated regions in the United States. 'Frontcountry' is a photographic account of people living in the midst of a mining boom that is transforming the modern American West.

Ranching and mining in the American West have had parallel histories and a common landscape. Cowboys and ranching culture are the chosen representatives of the region. Men on horseback ride through countless movies. But, the biggest profits are in mining. Though miners haven’t found any raw nuggets for generations, the American West remains one of the largest gold producing regions in the world. Companies are digging increasingly bigger holes to find smaller deposits, leaving pits where there once were mountains.

Alex Maclean - Agriculture, Arid Lands

Cart Path, Las Vegas, NV, 2009 Kentucky Canola Field, Hopkinsville, KY, 2016 Streaks Down the Radius, Hopkinsville, KY, 2016 Desert Housing Block, Las Vegas, NV, 2009 chromogenic prints, 40 x 60 inches

Millee Tibbs - Mountains + Valleys, 2013

Yellowstone #4, 23 x 35.5 inches Canyonlands #1, 23 x 34 inches Yellowstone #1, 23 x 16.5 inches archival pigment prints

Mountains + Valleys uses images of the American West as a starting point to interpret and confront cultural myths surrounding the representation of that landscape. Titled for the two primary folds in Origami, the work uses physical alterations to create relationships between formal geometries and natural spaces that question the illusionistic representation of the photographic image. Tibbs traveled to these sites to photograph them and then printed the images, folded them, and then re-photographed them. These images are simultaneously manipulated and yet photographically real. The geometric impositions onto the photo-object impress an aesthetic ideal onto the landscape, scarring the very thing they attempt to embellish. The fantasy of an untouched and untouchable vista is interrupted.

Griselda San Martin - The Wall, 2018 inkjet print, 20 x 30 inches

At the juncture of San Diego, California, and Tijuana, Mexico, the border wall’s rusting steel bars plunge into the sand, extending 300 feet into the Pacific ocean and casting a long and conflicting shadow. The Wall is a documentary project about “Friendship Park,” a stretch of the U.S.-Mexico border where families meet to share intimate moments through the metal fence that separates them.

Physical borders create symbolic boundaries that reinforce the rhetoric of “us versus them,” in which immigrants are seen as a threat to traditional narratives ingrained in various communities across America. The existence of these fences illustrates anti-immigrant sentiment, legitimizing exclusionary practices and justifying harsh government action. Once erected, they become enduring, permanent features of the geopolitical landscape—and a powerful, aggressive reminder to immigrants that they don’t belong.

By calling attention to the human interactions at Friendship Park, where families visit with and speak with one another through a metal fence, San Martin attempts to neutralize what this wall was built to create: Separation. Her goal is to transform the discourse on border security into a conversation about immigrant visibility, addressing audiences on both sides of the wall by challenging popular assumptions or by reminding them that they are seen, heard and that they matter.